By Stephen Mills

Everyone has heard about the workhouse. It’s generally viewed as a place of hardship, misery, and absolutely the last resort for desperately poor people. And that was true for many workhouses, especially those in and around the major cities. But in some places, although life in the workhouse might be hard, it was not necessarily as brutal and soul-destroying, especially in more rural locations such as ours.

But how were the parish’s poor helped before the advent of the workhouse? Often, they were ‘farmed’, where a private contractor undertook to look after them for a fixed annual amount. Able bodied paupers were expected to work, helping to contribute towards their upkeep. In other circumstances, the meagre wages of the poor were supplemented from parish funds, the amount given depending on the price of bread at the time, and the size of the particular family.

However, in 1835, all of the parishes in England and Wales were formed into what were known as Poor Law Unions, each with its own workhouse, and each managed by a Board of Guardians, usually made up of the local great and good. By the 1840s, hundreds of workhouses had been built across the country. Each Union provided a single workhouse to accommodate anyone unable to support themselves.

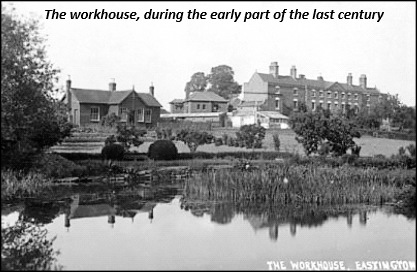

Eastington was actually ahead of the game, as ‘our’ first parish workhouse pre-dated these developments, having been built in 1785. When the Poor Law Union was formed, it was enlarged, becoming the Wheatenhurst Union Workhouse. It was designed by architect Mr Fulljames, who was also responsible for the Dursley Union Workhouse. Day-to day operation now fell to an elected board of eighteen governors, who represented the various parishes covered. These included Eastington, Brookthorpe, Arlingham, Frampton, Fretherne, Frocester, Hardwicke, Harescombe, Haresfield, Longney, Moreton Valance, Standish and Whitminster.

Unfortunate people could end up in the workhouse for a multitude of reasons – some were ill or infirm, and others were suffering from various forms of mental illness. In some cases, girls were there for simply being an unmarried mother. Some were temporary residents, whereas others were essentially there for the rest of their lives. In 1861, long-term residents in ‘our’ workhouse were classified as ‘idiotic, insane or infirm’. These included the ‘idiot’ Sabina Browning, who had lived in the workhouse for 24 years, and the ‘insane’ Mary Humphries who had been there for 14 years. Infirm residents had been there for between 5 and 24 years.

The census of 1881 makes interesting reading and helps paint a picture of life at the time. The Master of the workhouse was now Walter Coleman, with his wife Clara as Matron. There was also a porter and a cook on site. There were 72 residents, with ages that ranged between little one year old Thomas Wintle and 87 year old Celia Banks from Fretherne. Residents’ former occupations are listed where appropriate and include waterman, labourer, servant, farm labourer, drover, carpenter, sailor, nurse, and needlewoman, a true cross section of working class society. The residents various handicaps are classified, this time including blind, and deaf and dumb. But once again, a surprising number are simply tagged ‘imbecile’.

Their numbers included 28 year old former servant Mary Bateman along with 4 year old Rose, 7 year old John, and 9 year old Louisa – one wonders what their story was. Then there was farm labourer George Gorin with what appears to be seven family members aged between 7 and 22. Two (aged 16 and 18) were noted as being deaf and dumb. What tragedy put them in the workhouse – was it family bereavement or simply being too poor to put enough food on the table? There were also individuals such as 70 year old needlewoman Prisilla Woodman from Frampton who may have been too poor or frail to look after herself. And there was former waterman James Banks, now 69 years old and blind.

In 1894, an old Eastington resident recalled that in earlier years, a number of needy local families had been ‘given papers’ to be taken in by the workhouse by Henry Hicks, Lord of the Manor. The families moved in but continued going out to work; their children also went to work in the village cloth mills. It seemed as if they continued to live their normal lives, but usefully, without the need to find the rent.

In some places, the Guardians continued with the often harsh conditions imposed by some of their predecessors. But by and large, inmates of our workhouse were treated more kindly. The kindness extended to various events laid on for them during the year. This included a Christmas entertainment, funded by the local gentry. For example, in 1891, it was recorded that:

“foremost, as always on these occasions, were Mr James T Stanton [of The Leaze, now Eastington Park] and his family, and also the family of the Rector of the parish. A Christmas tree (“well laden with fruit”) was provided and gifts distributed by the Stantons to all residents. After, there was an evening of songs, music, readings and so on, “much to the enjoyment of the simple company”.

The workhouse continued to operate for some time and a fascinating insight into its later years was provided by the memories of the late Sylvia Bliss (see the ECN article here)

But the end was in sight. Gradually, the public attitude towards poverty began to change as the state began to accept more responsibility for social welfare, and in 1930, the Unions were finally abolished. Many either closed or were converted to community hospitals or old people’s homes. Eastington’s stood empty for some years, before finally transforming into William Morris College. So, this landmark building continues to serve the community well into yet another century. Its use may have changed, but it carries on fulfilling an equally important role.

Harry Butler – the workhouse milkman in 1907

You must be logged in to post a comment.