Whalebone arches are one of those odd things that pop up in various parts of the world. They usually consist of a whale’s jawbones. Examples in the UK include Whitby, the Isle of Lewis, and Edinburgh. Farther afield they can be found at Isafjordour in Iceland and even a double one in the Falklands Islands. Sometimes they reflect a local history of whaling, whereas in other places, they are simply erected as a novelty or have some other local connection.

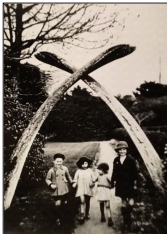

As many older residents of the village will already know (but many newer ones may not) is that Eastington also once had one. It’s been mentioned in several previous ECN articles (156 and 169) that described Alkerton House, a substantial dwelling with grounds that was replaced by Swallowcroft. The arch formerly stood in the garden close to the house, and for many years was a notable talking point for visitors and a well-used spot for photographers.

But what were the origins of Eastington’s arch? After all, we’re not exactly known for our history of whaling – we don’t often get whaling ships coming up the river Frome! Although there seems to be no document trail, our arch reputedly came from a whale that became beached on the banks of the River Severn at Littleton-upon-Severn near Thornbury in January 1885.

The event became an overnight sensation and thousands of people flocked to see the unfortunate creature which by now, had been hauled ashore using chains coupled to steam traction engines brought in from nearby Olveston.

Understandably, it caused a lot of local interest, but also attracted sightseers from farther afield. The Midland Railway even ran special excursion trains from Bristol to Thornbury, the nearest station, and at times, there was reportedly a three-mile tailback of carts and carriages trying to get to the site. No-one is sure of the total number of visitors, but one newspaper suggested more than 20,000!

A few weeks after the whale beached, Hector Knapp, a local fisherman from Oldbury, recorded in his diary:

“Thear was a Whal cum ashore at Littleton Pill and bid thear a fortnight. He was sixty eaight feet long. His mouth was twelve feet. The queen claim it at last, and sould it for forty pound. Thear supposed to be forty thousen pepeal to se it from all parts of the country and from far and near.”

Amongst the many visitors was a local Methodist preacher who, in order to verify the Bible story of Jonah and the whale, decided to see if it was possible for a man to stand upright inside the whale’s mouth – apparently he could.

And what became of the whale? After some dispute over ownership, it was eventually claimed by the Crown and towed by a tug down the Severn estuary then up the Avon. It finally came to rest in St Phillip’s Marsh in Bristol where it was exhibited to thousands more visitors before being made into fertiliser. Some of the whale’s bones were reportedly donated to the British Museum, although the jaw bones somehow made their way to the garden of Alkerton House. I can only image how difficult transporting them must have been – many years ago I helped move them and can confirm that they are very heavy!

Alkerton House was eventually demolished and the arch disappeared, only to come to light many years later in Whitminster – it’s now stored in Eastington. Hopefully one day it will re-emerge.

Note: You can find out more about the whale’s story by visiting Thornbury Museum.

Stephen Mills

You must be logged in to post a comment.